Dignity Kitchen in Boon Keng: Food court run by the differently abled dishes up hearty fare

- Project Dignity is the world’s first formal training centre for hawker hopefuls

- The social enterprise caters to differently abled workers with its train-and-place programme

- Its halal-certified food court in Boon Keng sees a healthy crowd of diners who return for its affordable, hearty food

It’s lunchtime, and the food court at 69 Boon Keng Road is a hive of activity.

The queue stretches to the main door and beyond, with office folks and workers from the nearby industrial district waiting patiently in line.

At first blush, it looks like any kopitiam. There are the usual suspects: Chicken rice, nasi lemak and laksa.

Oh, claypot rice… and is that the smell of freshly baked muffins?

If you’d missed the prominent mural at the entrance, this is Project Dignity, the world’s first training centre for hawkers.

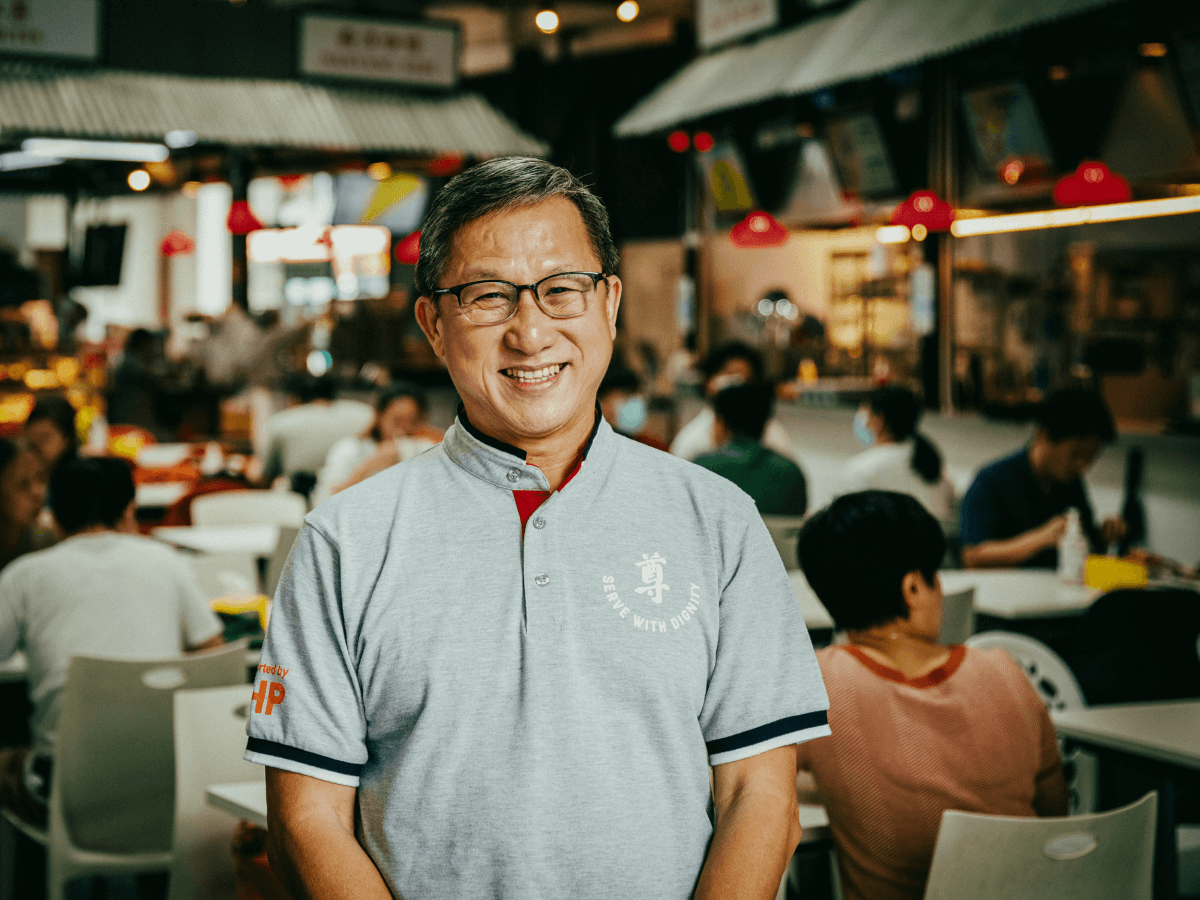

“You’ll see schools for formal culinary education and fine dining, but none for hawkers,” says Koh Seng Choon, executive director of the social enterprise.

It seems only fitting, then, that the home of hawker culture — now inscribed on Unesco’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity — has codified this into a curriculum.

Those who train here learn the ins and outs of running a hawker business. This entails not just cooking from recipes, but runs the gamut from the intricacies of taste, flavour and mouthfeel to dealing with customers.

The mission

What makes this place stand out all the more: It also caters to those who are differently abled.

Dignity Kitchen — Project Dignity’s food court arm and Asia’s first community food court managed by people with disabilities — offers work opportunities to more than 100 workers, of whom 85 to 90 per cent are differently abled.

If there’s one thing that’s clear during our visit, it’s that not all disabilities are visible.

[google_ad]

Uncle Peter, who works at the drinks stall, signs cheekily at us with a big grin — visible even through his face mask.

The hearing-impaired 65-year-old brews a mean cuppa. As he stirs, spoons and pours, he walks us through some basic signs with a smile.

He’s paired with an able-bodied worker who helps him when the situation calls for it — typically signing him drink orders from customers who aren’t familiar with sign language.

The social enterprise welcomes all who are differently abled and disadvantaged, including the disenfranchised.

Koh says: “It can be physical, like the loss of a limb in an accident. It can be mental (such as) depression and bipolar disorders. There’s a social element, too — single mothers, abuse cases — and, lastly, the intellectual aspect — those with IQ 70 and below.”

The idea is to skill people who need help, so they can get jobs elsewhere.

Using tech

Besides breaking down the nuts and bolts of running a hawker business, Project Dignity takes it a step further by simplifying the process with technology, where possible.

At the claypot stall, for instance, the ingredients are prepared beforehand. The assigned worker puts the necessary components into a pot, places it on the stove, and waits for the timer to go off before serving a piping-hot claypot meal.

Instead of a traditional claypot stove, the system relies on electricity with no open fires, thus improving workplace safety and reducing ambiguity.

The latter is especially important, says Project Dignity. Some workers on the autism spectrum are most comfortable with a strict set of steps and do not deal well with deviations.

This system also allows an amputee worker to man the stall solo.

Creating a hospitable work environment is also key, Project Dignity adds. The intention is to reduce stress for the workers, where possible, as well.

Stoves and other similar equipment tailored to the differently abled are a challenge to obtain, and Project Dignity relies heavily on donations and sponsorships from external parties to make this possible.

What’s on the menu?

Besides claypot rice (S$6), Project Dignity’s signatures include kolo mee (S$5), laksa (S$4.50), nasi lemak (from S$4.50) and chicken rice (S$4).

Dignity Kitchen’s low prices and hearty food seem to have its customers returning for more.

Many of the diners are regulars — workers and office folks from nearby industrial districts or those who live in public housing blocks in the vicinity.

You’ll also find the mouthwatering smell of vanilla and butter wafting through the air. Muffins, cakes and even seasonal specials such as stollen and log cake are churned out of its oven throughout the day.

The food court is also halal-certified, and sees healthy demand from corporations for its bakes and takeaway items, especially during Christmas and Chinese New Year.

Like any F&B business out there, even a social enterprise like Project Dignity has its grouses and unhappy diners to deal with.

Cheryl Loh, events and social media assistant for Project Dignity, says: “Most customers are patient, but sometimes, we get angry customers who aren’t aware that the workers are differently abled.”

Beyond just hawkers

Project Dignity’s main objective is its train-and-place programme, so that its trainees can support themselves in the long run.

Says Koh: “After skilling them, we must get them jobs. Some of them work here; some in cafes, hotels. If we cannot get them jobs elsewhere, we create jobs for them here.”

This is also where the other projects under the Dignity umbrella come in. Apart from Dignity Kitchen, there are others including Dignity Wheel — where wheelchair users do short-distance food delivery — and Dignity Craft, a group of enterprising ladies who knit caps for cancer patients.

There is even Dignity Avatar, which trains workers with physical disabilities to operate robots remotely. These robots are deployed to hospitals here and in Hong Kong to ease the workload on healthcare workers.

Edible garden

Just a stone’s throw from the main dining area is Dignity Farm, a hydroponic urban farm that grows a multitude of leafy greens.

Adriel Yeo, 24, is one of the folks manning it.

He has had some experience in growing plants of his own, but still finds certain ones, such as fennel, a challenge to grow.

As is keeping the irrigation system mosquito-free — a task that sees him meticulously monitoring the flowing water with a fine fish net, in search of potential larvae.

Some of the crops, such as spring onion and rosemary, are used in the kitchen, and occasionally, in the training courses that Project Dignity runs.

Yeo, one of the longest-serving folks on the farm, has been with the social enterprise for slightly over a year. He also works on human resources and accounting tasks in the small office above the farm.

Hot off the stove

Round the back of the compound is a hot kitchen, much like what you’d see in any bustling restaurant.

This is where the social enterprise cooks up food in big quantities, mostly for its catering arm, which turns out an average of 300 bentos daily.

To mitigate the usual dangers of a working kitchen, those assigned to work here are higher-functioning and guided by experienced culinary professionals.

Housemade rempah and rendang are also made in large quantities here — from scratch — and used in Dignity Kitchen’s hawker dishes.

Making it all work

For Koh, the brains and heart behind the operation, charity work has been a big part of his life for the past two decades. Earlier this year, he was named a Champion of Change by the World’s 50 Best Restaurants.

It’s been quite the journey — the operation was bleeding money in its initial years before breaking even in 2016.

Since then, the profits have been put back into its people. Trainees are paid a wage of S$6 an hour, and the organisation gives a free hot dinner to almost 100 of the working poor every night.

A lot of the funds also go towards Project Dignity’s Hong Kong outpost, which employs more than 50 workers.

What’s next for Koh? An outpost in London for war veterans and refugees. And, beyond that, for Project Dignity to become a publicly listed company.

Book a ride to Project Dignity.

Dignity Kitchen

69 Boon Keng Road

Nearest MRT station: Boon Keng

Opens: Mondays to Fridays (8.30am to 4pm), Saturdays and Sundays (8.30am to 2pm)

69 Boon Keng Road

Nearest MRT station: Boon Keng

Opens: Mondays to Fridays (8.30am to 4pm), Saturdays and Sundays (8.30am to 2pm)