What to say for lo hei & yu sheng’s history in Singapore

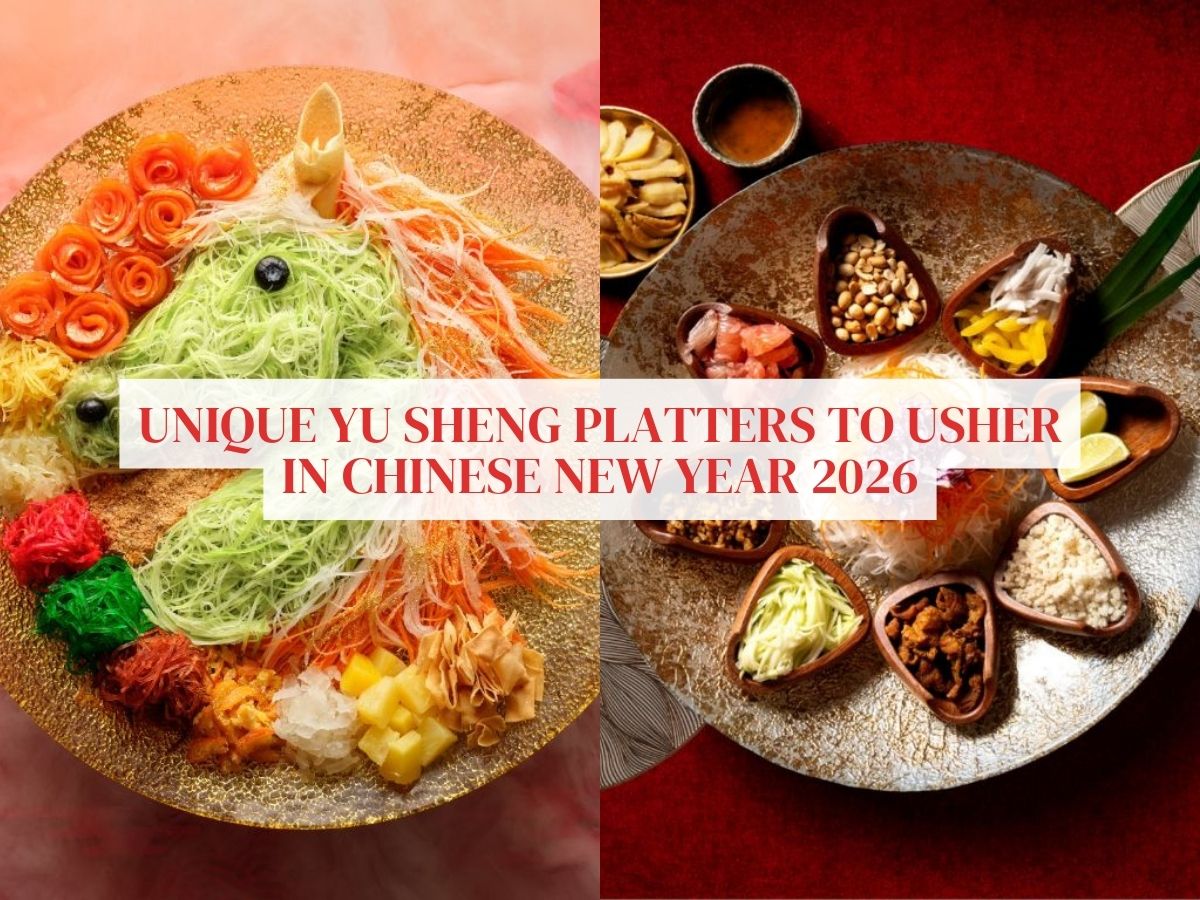

As families across Singapore prepare for Chinese New Year celebrations, preparing to dig into a variety of meals, every table would most likely have one dish in common: Yu sheng.

No matter the nature of the meal, from an intimate family dinner or a larger-scale corporate meal, the colourful raw fish salad is bound to take centrestage, with everyone often partaking in the act of “lo hei” (Cantonese for “tossing”), where the ingredients are tossed in the air for good luck and fortune.

If you’ve always been at a loss on what lo hei sayings to dole out as the yu sheng platter is assembled, or wondered how to explain to curious non-locals how this Chinese New Year tradition came about, we’re here to help.

A brief history of yu sheng

While lo hei feels like an age-old custom many of us grew up with, few might have known that this practice of having raw fish in Chinese cuisine actually dates back over two millennia, with records of such dishes existing from as early as 823 BCE.

It was said that in the past, fishermen in some cities in Guangzhou, China would consume raw fish mixed with sauces, shallots, and shredded vegetables on the 7th day of Chinese New Year. (This day is known as “ren ri” and is celebrated as the birthday of all humankind.)

The dish was called “yu sheng” even back then, stemming from a combination of the word “yu”, which can mean fish (鱼) or abundance (余), and “sheng” (生), which also has a double-meaning of “raw” or “life”. Taken together, consuming yu sheng meant you’d get an abundance of fortune and life.

When Cantonese and Teochew immigrants arrived in Singapore and Malaysia during the 19th century, they brought over the dish, along with the practice of tossing it on ren ri, however the yu sheng of today isn’t quite like that of the yesteryear’s.

A Chinese tradition reimagined in Singapore

The yu sheng that most of us know of and consume today came about around the 1960s, with its creation often credited to four local chefs, affectionately dubbed the “Four Heavenly Kings” of Cantonese fare in Singapore then: Tham Yui Kai, Sin Leong, Hooi Kok Wai, and Lau Yoke Pui.

Instead of the plainer, simpler version brought over by the early Chinese immigrants, the quartet elevated the dish, incorporating colour, texture, more ingredients, as well as aromatics.

Their creation, the seven-colored raw fish salad, was introduced to various communities though clan associations and community centres among others, and paved the way for different variations of yu sheng to come about.

While simple auspicious phrases used to be called out when yu sheng was tossed, people soon began spontaneously associating the various ingredients with their own well-wishes, expanding the lo hei ritual’s vocabulary of prosperity.

In some ways, the lo hei that we know and love in Singapore today, the dish and its rituals, is truly a tradition that’s been maintained and furthered by the people.

And as the lo hei sayings multiplied, so the types of yu sheng you see being sold and prepared today.

Today, it is not uncommon to see versions with abalone, beef, or even lobsters in lieu of raw fish in yu sheng. Vegetarian versions, sometimes with mushrooms and fruits, have also made their way to menus, to cater to growing dietary preferences.

Your guide on what to say for lo hei during CNY

With such a multi-faceted history, as well as increasingly differing ingredients, it’s clear that there is no “proper” way for one to lo hei, though there is often a basic sequence of ingredients steps.

In Singapore, the person adding the ingredient to the platter (whether it’s the server at a restaurant, or a family member) usually utters a blessing in Chinese as they add each ingredient to the platter, with each blessing utilising clever wordplay to connect the food to fortune.

Those around the table are expected to respond “shou dao” (收到; received) or to repeat the phrase, to accept the well wishes.

Not sure what lo hei sayings to use? Here’s your fuss-free guide that’ll help you impress even the most difficult of elders:

1. Setting the stage as the platter arrives

Say: Gong xi fa cai (恭喜发财; wishing you wealth and good fortune) or wan shi ru yi (万事如意; may all your wishes be fulfilled)

Why? You’ll want to kick things off with general auspicious greetings to set an optimistic tone for the ritual ahead.

2. Lay the foundation with raw fish

Say: Nian nian you yu (年年有余; May you have abundance every year)

Why? This phrase capitalises on the homophone between yu (鱼; fish) and yu (余; surplus), and wishes everyone abundance and surplus in the year ahead.

3. Squeeze in some citrus sunshine

Say: Da ji da li (大吉大利; may you have great luck and prosperity)

Why? Citrus fruits hold a special significance in Chinese tradition for its association with luck and wealth, with the pomelo being particularly significant.

You’ve probably noticed the character ji (吉; luck) plastered on pomeloes during this festive season. This is because the Mandarin word for pomelo, you zi (柚子), sounds similar to the phrase you ji (有吉; to have luck), making the fruit a powerful symbol of good fortune.

4. Dust on the spice of life

Say: Zhao cai jin bao (招财进宝; may you attract wealth and treasures) or wu fu lin men (五福临门; may the five blessings descend upon your home)

Why? The dramatic sprinkling of pepper and five-spice powder (often in green and red sachets) represents wealth spreading far and wide.

The phrase wu fu lin men specifically references the five-spice powder (since both mention “five”), wishing diners longevity, wealth, health, kindness, and peace upon their home.

5. Drizzle the oil in circles

Say: Yi ben wan li (一本万利; may your capital bring you ten-thousand-fold profits) or cai yuan guang jin (财源广进; may your sources of wealth bring you great prosperity)

Why? Pouring the oil a circle to symbolises a multiplied growth in profits and it also acts as a visual representation of wealth flowing in endlessly from all directions.

6. Paint the platter red with shredded carrots

Say: Hong yun dang tou (鸿运当头; good luck is approaching)

Why? The Chinese word for carrots includes the word “hong” (红; red), which is a homophone for hong (鸿; great or grand), which points towards grand fortune knocking on your door.

7. A splash of eternal youth with green radish

Say: Qing chun yong zhu (青春永驻; may you remain forever youthful)

Why? The character for greens in Chinese is “qing” (青; green), which is the same as the first word of qing chun (青春; youth), essentially symbolising health and beauty.

8. Layer on success with the white radish

Say: Feng sheng shui qi (风生水起; may you progress quickly) or bu bu gao sheng (步步高升; may you rise to greater heights)

Why? While yu sheng is a dish with mainly Cantonese origins, many Singaporean-Chinese are of Hokkien descent and may have associated the Hokkien name for white radish, “chye tow” (菜头), with the Chinese phrase “彩头” (cai tou) due to its similar pronunciation.

With cai tou being associated with good luck, the addition of the vegetable to the platter began to symbolise the smooth ascent of the career ladder.

9. Shower the platter with crushed peanuts

Say: Jin yin man wu (金银满屋; may your house be filled with gold and silver)

Why? As the golden-brown peanut bits rain down onto the salad, they’re meant to signify treasure that covers the yu sheng in symbolic wealth.

10. Sprinkle on corporate success with sesame seeds

Say: Sheng yi xing long (生意兴隆; may your business prosper)

Why? Similar to the crushed peanuts, the copious amounts of sesame seeds are meant to symbolise the abundant success of a flourishing business.

11. Top it all off with golden pillows

Say: Man di huang jin (满地黄金; may your floor be covered in gold)

Why? The crispy, golden flour crisps often come shaped like gold ingots and as the finishing crisps are added to the yu sheng, usually in large amounts (because who doesn’t like some crunch?), it symbolishes a final touch of prosperity for everyone.

12. Bind it together with sweet plum sauce

Say: Tian tian mi mi (甜甜蜜蜜; sweet as honey)

Why? Unlike the other blessings that wish for an abundance in fortune, this particular ingredient wishes for family unity and harmony.

The often-sticky plum sauce acts as a “glue” to bind the salad ingredients, symbolising how a unified family and strong relationships are the key towards holding everything together.

And that’s it!

As you toss the ingredients, it is not uncommon to pepper shouts of “huat ah”, which is Hokkien dialect meaning “to prosper”, or to add your own Chinese blessing, as a wish for yourself in the new year.

It is believed that the louder you shout and the higher you toss, the more prosperous your year will be, so don’t worry too much about the mess, it’s part of the experience.

So, as you partake in the tradition of lo hei and dig into your yu sheng this coming Chinese New Year, we hope you’ll see that it’s really more than just a dish.

It’s become a uniquely Singaporean-Chinese ritual of shared optimism where communities come together, tossing wishes of abundance into the air (and sometimes to each other), ushering in the anticipation, joy and prosperity of the new year, and that it itself is also something worth cherishing and celebrating.

Happy Chinese New Year and 恭喜发财 from all of us at HungryGoWhere!

If you still need to grab a yu sheng platter, check out our yu sheng platter shortlist, and if you’ve yet to find a place for your festive dinner, we have just the guide, too.