On the Table: Where has all the char kway teow gone?

On the Table is a new HungryGoWhere series about the stories behind Singapore’s plates. It dives into the “past lives” of our food and the people who keep it alive today.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in Tampines Mall and the food court feels like it’s been scrubbed of heritage: Stainless steel counters, LED menus, and signboards that use the same ol’ boring fonts. I order the chicken rice, but what I really want is char kway teow.

Then I think to myself, “It’s quite rare to find the dish in food courts nowadays, huh.”

Some malls might still have a stall selling char kway teow, but it’s no longer a guarantee. More often, it’s the domain of older hawker centres or the occasional neighbourhood kopitiam.

It’s not that it’s disappeared completely – but it is no longer something you expect to see everywhere.

Now, I wouldn’t consider myself a connoisseur of char kway teow, by any means. But the dish has been a kind of comfort since I was young — something my parents would bring home at least once a week.

The memories are even more vivid when I think about the late-night suppers with my schoolmates at Chomp Chomp Food Centre. It starts with the smell — smoky, porky sweetness in the humid air, then the loud clang of metal against wok and flames billowing out. If you’ve been to the hawker centre prior to its 2017 renovation, you’ll know how smoky the whole place gets, but that simply contributed to the experience.

You can still find glorious renditions: Outram Park, Hill Street, and Quan Ji are some I’ve tried, and they’re as good as ever. But quality char kway teow such as these are getting far and few between.

More likely you’ll find a just-okay $5 plate from a coffeeshop stall with no personality. These usually miss the punch, and you find yourself eating the idea of char kway teow more than the real thing. Pork lard is sparse, cockles are MIA, and the slightest touch of wok hei, if any at all.

A dish for the hard and hungry

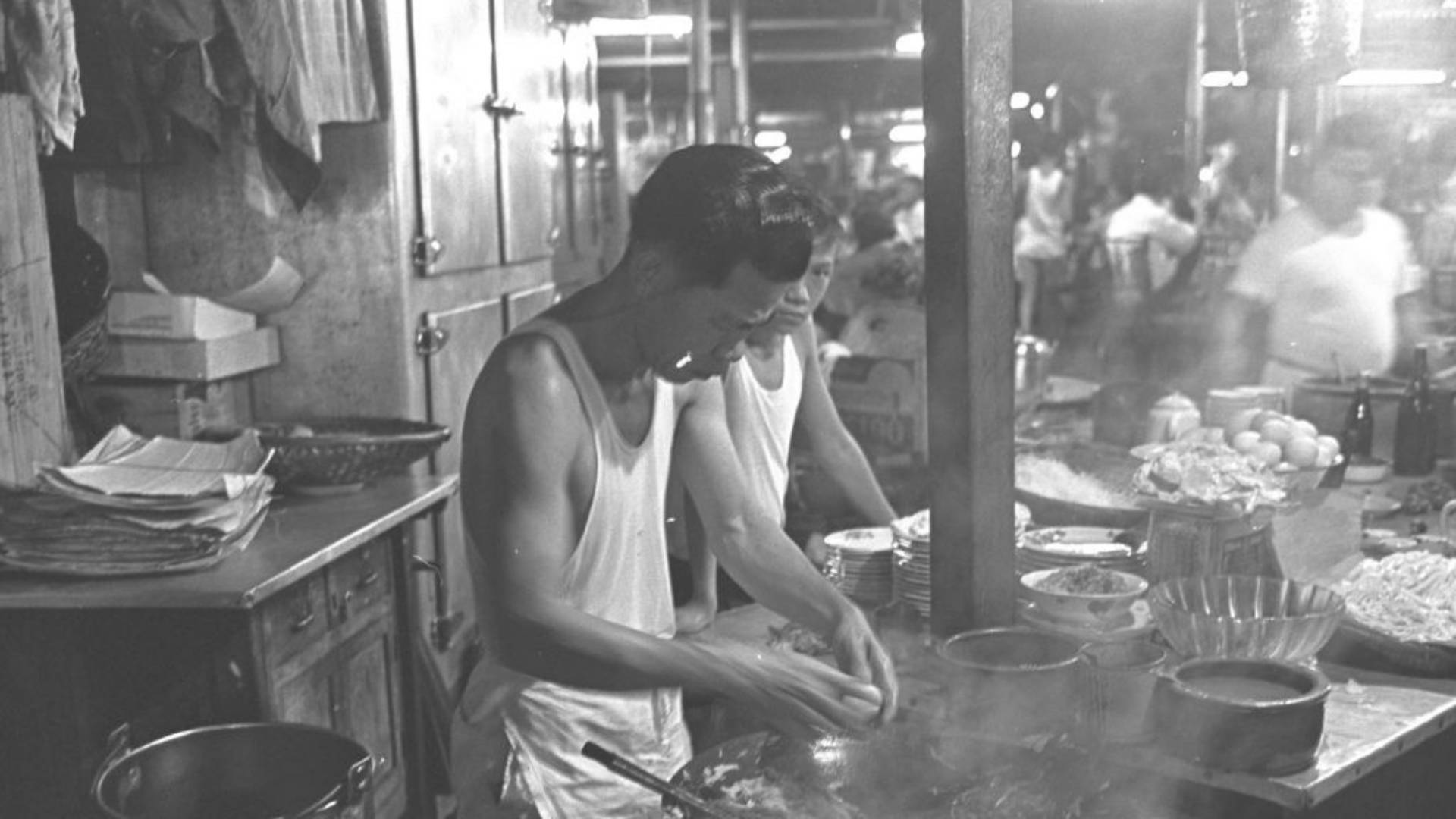

Char kway teow was always about sustenance. In the 1950s and 1960s, Teochew and Hokkien hawkers fried it over charcoal fires for dock workers, coolies, and trishaw riders — basically, men who laboured all day and needed something hot, fast, and cheap.

Flat rice noodles and bean sprouts were cheap, cockles were abundant and inexpensive, and pork lard added both calories and depth of flavour. Sometimes there’d be slices of Chinese sausage, and a few prawns, if you were lucky.

The earliest char kway teow hawkers were often travelling around, wheeling their charcoal stoves and ingredients from alley to alley. Soy for salt and umami, dark soy for sweetness, a pot of chilli, and another for lard. The best ones came slightly charred at the edges, where the soy sauce caramelised and crisped up the noodles.

By the late 1980s, char kway teow had slid into nearly every hawker centre, with each stall boasting its own signature riff — some sweet and dark, some flavoured with cockle juice, some so wet and silky it almost slid down your throat.

Regardless, for a long time it was a dish that everyone could easily access. It was filling, deeply satisfying, and everywhere. So where did it go?

Delicious, but unhealthy (and difficult)

Char kway teow may have been added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, but in Singapore, its prominence as a national dish feels less assured, compared to chicken rice, laksa, or nasi lemak.

In the early 2000s, the Health Promotion Board launched campaigns urging Singaporeans to eat less fat, salt, and oil, and local media began classifying hawker food as unhealthy or even “dangerous” in its indulgence.

Char kway teow wasn’t necessarily public enemy No. 1, but it definitely made the top of the “most unhealthy” lists.

It might be for this reason that I don’t think anyone has ever asked me about where to find the best char kway teow in Singapore — tourists aside, the dish simply wasn’t in the minds of locals who ate at coffeeshops and hawkers almost daily.

In fact, if you ask your friends and family what the most unhealthy hawker dish is, I’d bet most of them mention this one.

To counter the bad rep, more stalls began tweaking their recipes. Lard was the first to go, then the cockles, increasingly viewed with suspicion (undercooked ones had the risk of giving mild food poisoning or even hepatitis A).

At Golden Mile Food Centre’s 91 Fried Kway Teow Mee, the stall is famous for topping its char kway teow with a mound of chye sim, and for not using pork or lard, at all. In this, they’re not alone. There’s also Heng Huat Char Kway Teow at Pasir Panjang, where the hawker has been quietly doing a similar version for well over 30 years.

When I visited 91 Fried Kway Teow, I noticed the curtain of newspaper clippings and food reviews — and even a screen. While queuing, I remarked to the lady boss how good the noodles tasted (this was my third or fourth repeat visit), even without lard.

She ignored me for a few seconds, then said in Mandarin: “We use a special broth that takes a long time to cook. You try first.”

The texture is good: It’s less oily and better than most run-of-the-mill HDB coffeeshop char kway teow. But the taste lacked that knockout punch.

Old guards, and a new generation coming up

At the same time, in the early 2000s, urban renewal was changing the hawker landscape. Cooking over charcoal was pretty much non-existent (the only place I know of that still cooks char kway teow this way is Choon Hiang).

Elderly hawkers began retiring, and their children, faced with the reality of sweaty and hot 10-hour days, chose office jobs instead.

After all, cooking good char kway teow is a physical act. The wok must be searing hot, the ingredients are stirred with speed and strength. Too slow and the noodles clump; too fast and it’s undercooked. Achieving the desired amount of wok hei is a whole other skill.

Many of the OG stalls still exist today, but there is noticeably less fire burning in Singapore’s char kway teow scene.

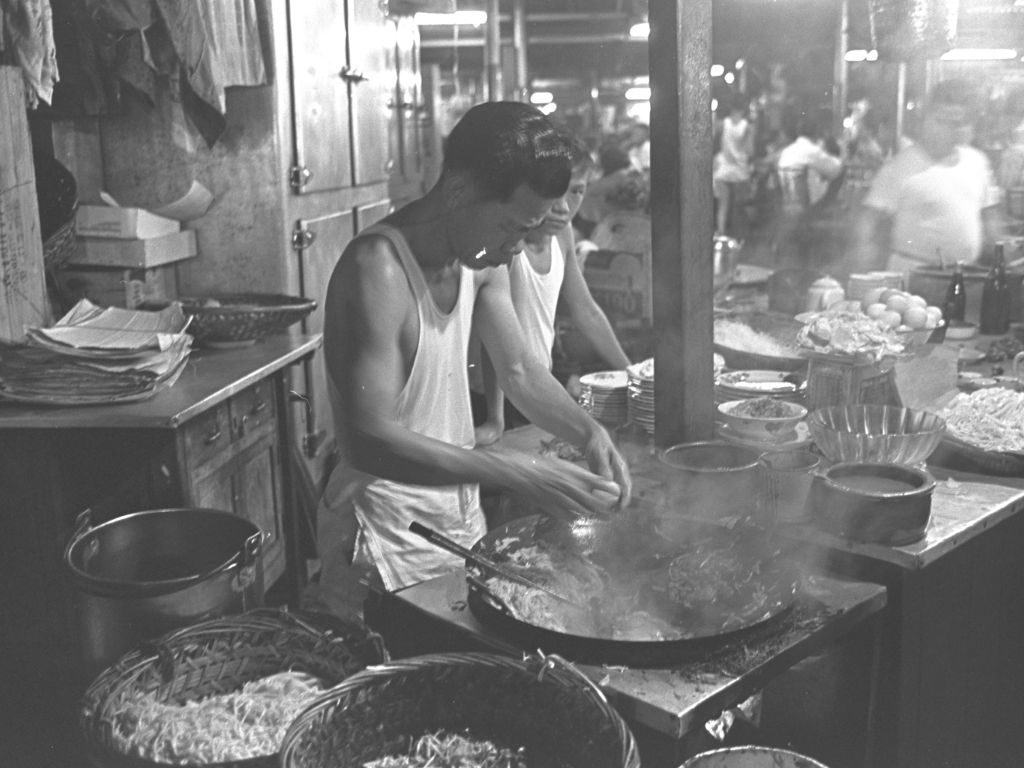

On a Friday morning at Michelin Bib Gourmand-awarded Outram Park Fried Kway Teow, the queue snakes around to the back, along the walkway.

Ng Chin Chye, now 71, sweat-slicked in his signature white tee, cooks up to twenty plates at a time. You wait in line for around thirty minutes on a weekday morning, and your reward is that plate of silky, punchy noodles, slicked with tangy-sweet chilli. The wok hei is not as apparent here, which might be due to the never-ending number of orders that come in.

While his two sons are now the third-gen successors of the business, Chin Chye still mans the wok, while they learn the ropes — to someday take the reins.

I strike up a short conversation with a regular behind me after he sees me taking photos, telling me that the sons sometimes take over the frying so that their father could rest, and the results are still pretty good.

A few streets down at Chinatown Complex Food Centre is the equally-beloved Hill Street Fried Kway Teow (not to be confused with the stall of the same name in Bedok), if slightly less well-known than Outram Park’s.

While Google lists its opening days as Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, I hear its opening hours are very fluid, due to the elderly owner’s many medical appointments.

The uncle has been cooking char kway teow for over 50 years since he was 17. Priced at S$4 and S$5, his version comes served on waxed paper and styrofoam. Compared to Outram Park’s smoother, wetter noodles, Hill Street gives you a dry char kway teow that’s cooked plate by plate for a more consistent char in every bite.

Just 2km away in a Bukit Merah coffeeshop, Dominic Neo is doing something a little different. The 51-year-old founder of Liang Ji Legendary Char Kway Teow, has spent the last few years cooking char kway teow that doesn’t pretend to be traditional — but pays homage.

He’s best known for his Instagram-ready “Humful” version, which comes overflowing with some 30 large blood cockles. Other variants include mala char kway teow, crab meat, and even an XO version with oysters.

Two office workers in front of me go for the “Humful”, but I order the mala. About five minutes later, he hands me a plate. The noodles are still blisteringly hot, tangled, studded with at least eight large cockles, and ribboned with mala sauce. It’s dry, not too sweet, and appetising as it is spicy.

While he also sells other fried dishes such as oyster omelette, carrot cake, and Hokkien mee, his focus is on char kway teow, hence the official stall name.

“It’s a Singapore heritage dish,” he tells me. “Plus, a lot of people like cockles.”

When asked about how his version differs from traditional char kway teow, he says: “A lot of people have opinions on what char kway teow should be, but mine is unique — transformed from classic, into fusion.”

It’s not easy being a hawker nowadays, he adds. “Creativity is important, and you have to be willing to accept failure, and upskill. Not just food, but marketing, operations — everything.”

Where does the wok go from here?

If the 20,000 members of the Char Kway Teow CKT Hunting Facebook group is anything to go by, there’s no shortage of foodies in Singapore still in love with the dish.

The question is: Will the lack of people willing to continue cooking char kway teow mean it might soon join the ranks of dishes such as Fuzhou oyster cake and satay bee hoon – disappearing almost entirely, except for a few select stalls islandwide?

Right now, I’m thinking it will survive, but it will likely look very different in a decade or two from now. There will be boutique renditions, healthier versions from young hawkers that decide to carry on the legacy of char kway teow with new takes, likely from within an air-conditioned food court.

Or maybe some second- or third-generation hawker inherits a stall and decides that the lard, the smoke, and the heritage is worth the sweat. Until then, the next time you smell that unmistakable marriage of soy and charred noodles deep in a hawker centre, somewhere, follow your nose and eat it like you mean it.